OPS245 Lab 3: Difference between revisions

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

* A '''comment''' - an unstructured string of text, usually used to store a user's full name. | * A '''comment''' - an unstructured string of text, usually used to store a user's full name. | ||

* The user's '''home directory'''. It's a sort of default directory for each user. You'll have noticed that it's the directory your shell is in when you log in, and it's what <code>~</code> and <code>$HOME</code> are set to. | * The user's '''home directory'''. It's a sort of default directory for each user. You'll have noticed that it's the directory your shell is in when you log in, and it's what <code>~</code> and <code>$HOME</code> are set to. | ||

* The user's '''login shell'''. You | * The user's '''login shell'''. You probably only ever used Bash, but there are several other shells which some people prefer. The differences mostly matter only to advanced users. | ||

== The password == | == The password == | ||

Revision as of 22:28, 27 January 2023

!!!THIS LAB IS NOT READY YET!!!

In this lab we'll look at the simplest types of user management on a Linux system.

What's a user

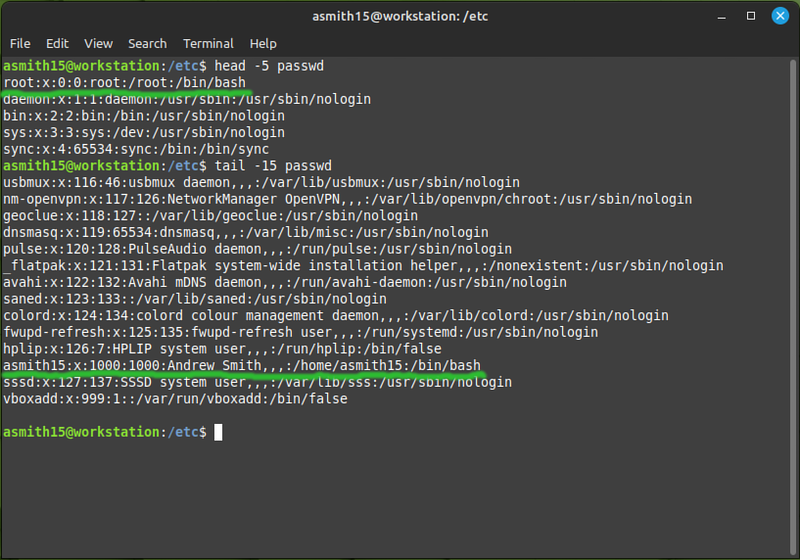

- Look at the contents of the /etc/passwd file:

Every line in that file is a user. Two of them you have used explicitly: root and your own username.

Each line is made of several fields, delimited by a colon. The same as a comma-separated value file (CSV) but separated by colons instead of commas. The fields are:

- The username (e.g. asmith15)

- A field that's no longer used, in the distant past it was the user's password

- The UID (user ID) - a unique number identifying the user. The system uses these numbers to determine who owns which files and processes.

- The GID (group ID) - the number identifying the user's primary group. Every user on a Linux system is a member of at least one group. It can be a member of other groups as well, but that membership is specified in the /etc/group file.

- A comment - an unstructured string of text, usually used to store a user's full name.

- The user's home directory. It's a sort of default directory for each user. You'll have noticed that it's the directory your shell is in when you log in, and it's what

~and$HOMEare set to. - The user's login shell. You probably only ever used Bash, but there are several other shells which some people prefer. The differences mostly matter only to advanced users.

The password

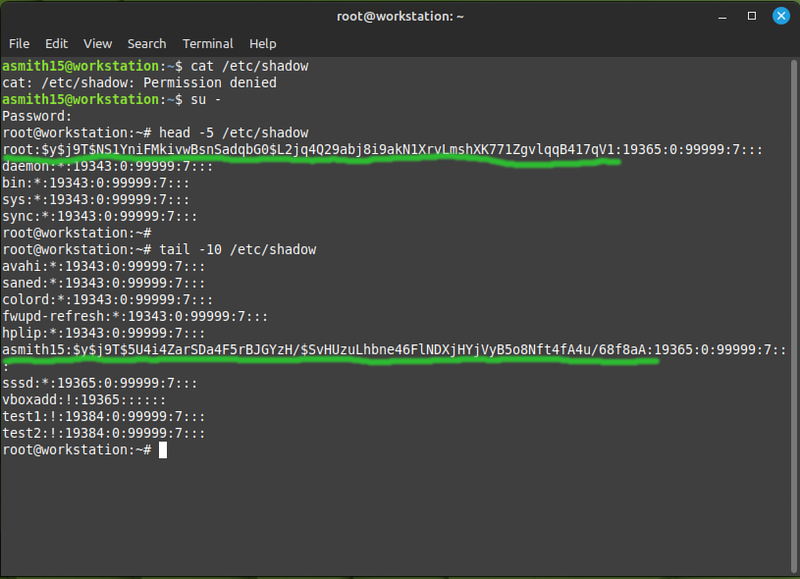

Linux users no longer have their hashed password stored in the /etc/passwd file. At one point the available computing power increased so much that the one-way hash could be reversed by brute force, therefore any user on the system could theoretically get any other user's password. To avoid this problem: the password hashes were moved to the /etc/shadow file which regular users don't have access to:

The long string of random-looking characters is not the password, it's a hash of the password. The idea with a hash is that you can convert some plain text into the hash, but you cannot convert the hash back into the plain text. You might think of it as encrypting something with no key to decrypt it, but it's a different process: a hash is a fixed size, and the data can be a million times larger than the hash - so it would be nonsensical to try and reverse the hashing process. That's why these days most services won't let you retrieve a forgotten password: it's simply not there to be retrieved, you have to reset it.

Home directories

- Regular users' home directories are /home/username. That is typical for regular users, but there are other types of user:

- The root user's home directory is /root. This is because traditionally the /home directory was on a storage device which was mounted (i.e. connected) at a later stage of the boot process. And if something went wrong with the boot process: having access to root's files was helpful for fixing booting problems.

- Services often have a home directory set to where they store data by default. For example the www-data user (the Apache web server runs as this user) stores web content in /var/www by default - and that's that user's home directory. For services the default home directory is mostly meaningless, they never use the $HOME environment variable.

Technically a valid user does not need to have any write access to their home directory. You could create a user with <code>/</code> for a home directory - and that user would work just fine, except it couldn't write any files in their home directory.

Create and modify users & groups

If you end up administering Linux servers: at some point you're going to create a user. Even if it's a server which only the administrator has access to: the services running on it may need users created for them.

There are two commands available to create a user. They sound the same and accomplish the same goal, but they are used in different circumstances:

- adduser is intended to be run in an interactive session, meaning that you're available to answer questions which it prompts you with.

- useradd can be run from an interactive session, or from a script.

Since I don't manage many users: I prefer the adduser command, it's easier to use for one-off situations. We'll use the useradd command because even though it's more complicated: it can be used in more situations.

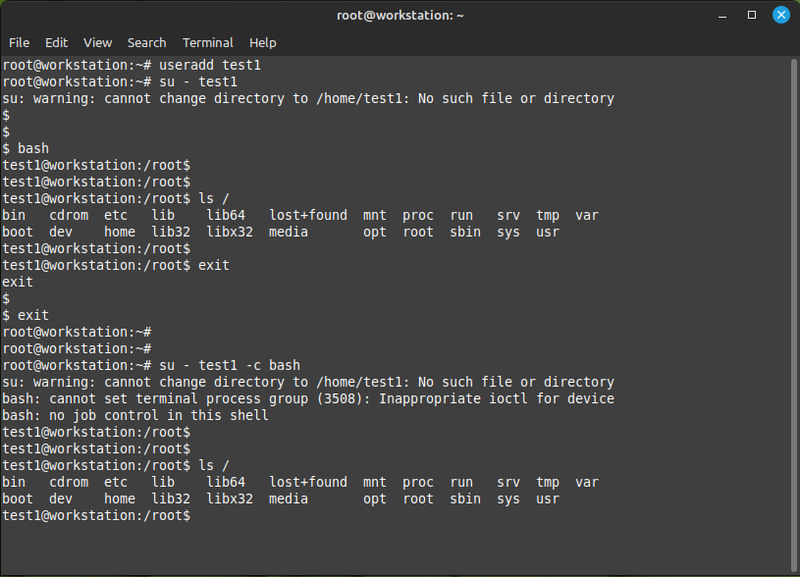

- On your workstation: create a new user called test1:

useradd test1

Notice that it didn't ask you for a password. At this point the only way to log in as that user is to first log in as root, and then switch to the new user. Notice also that test1 is missing its home directory, but you can still do most things you would expect to be able to do on the commandline. For some complicated reasons the shell environment doesn't look right, you can run bash after your su command, or you can tell the su command to run bash for you:

The colours in the prompt are missing because root's prompt doesn't have any colours, and test1 doesn't have any bash configuration files to set them.

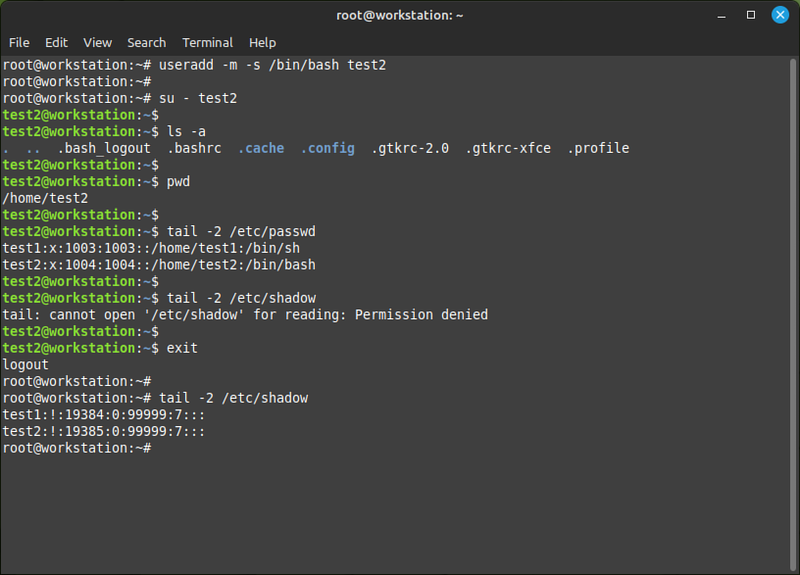

- Create a new user called test2, this time make sure a home directory is created for it:

useradd -m test2

The bash command starts a new shell which loads test2's bash configurations, so the prompt looks normal and the keyboard works properly.

- Look at the bottoms of

/etc/passwdand/etc/shadow. A couple of things are worth noting:- The UIDs are assigned sequentially, starting from 1000. User IDs less than 1000 are usually reserved for system (service) users and root (with UID 0).

- The two new lines in the shadow file have a ! instead of a password hash.

- Set a password for test2:

passwd test2

You are able to set another user's password because you're logged in as the superuser, who has permissions to do anything that's possible to do on the system. Try to run the same command as your regular user to see what happens.

Permissions

You should have learned about file and directory access permissions in ULI101. Those are Read, Write, and Execute for User, Group, and Others. Some quick reminders:

- The octal notation for chmod is not too complicated if you remember that read is 4, write is 2, and execute is 1. That gives you a range of possible combinations from 0 to 7.

- For a directory: read means list the contents of the directory, and execute means traverse the directory (cd into it or access any of its contents in any way).