OPS145 Lab 7 Newversion: Difference between revisions

(→Also:) |

|||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

[[File:LsIntoFile.png|center]] | [[File:LsIntoFile.png|center]] | ||

The reason why homecontents.txt doesn't have any colours in it is simple: there's no such thing as dark blue or light green in a plain text file. There's just text. The more complicated question is where did the pretty colours come from when the output is in a terminal? That's too complicated a question for this course, and we're just going to ignore it. | The reason why homecontents.txt doesn't have any colours in it is simple: there's no such thing as dark blue or light green in a plain text file. There's just text. The more complicated question is where did the pretty colours come from when the output is in a terminal? That's too complicated a question for this course, and we're just going to ignore it. | ||

== Redirect STDERR to a file == | |||

* Run an ls command, giving it as an argument a filename for a file which doesn't exist. For example:<syntaxhighlight lang="bash"> | |||

ls command.com | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

* The command prints some output: "ls: cannot access 'command.com': No such file or directory". From experience I know that this comes through the STDERR pipe, but we can confirm by redirecting STDOUT to a file:<syntaxhighlight lang="bash"> | |||

ls command.com > ~/lab6/lscommandcom.txt | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

* Note that the output is still printed in the terminal, and the file lscommandcom.txt is empty. There's really no way to see a difference between standard and error output except through experimentation like this. | |||

* You can redirect STDERR to a file using the '''2>''' notation (2 is the number of the pipe):<syntaxhighlight lang="bash"> | |||

ls command.com 2> ~/lab6/lscommandcom.txt | |||

</syntaxhighlight>[[File:STDERRtoFile.png.png|center|800x800px]] | |||

Here's what all that looks like: | |||

[[File:RedirectStderr.png|center]] | |||

Because there's no obvious difference between standard and error output in the terminal: this distinction often causes headaches, but that's just a reality we have to deal with. | |||

You can redirect STDOUT to one file and STDERR to another file: | |||

[[File:RedirectStdoutAndErr.png|center]] | |||

== Redirect to /dev/null == | |||

'''/dev/null''' is a special device file on Linux machines. It's like a black hole: anything that goes into it just disappears for ever. It is frequently used when you want to run a command, but you're sure you don't want to see the output of that command, and you don't want to save that output either. The utility of this will become more obvious when we get to scripting. | |||

For now you can practice with the ls command: | |||

[[File:RedirectToDevNull.png|center]] | |||

= Also: = | = Also: = | ||

| Line 59: | Line 85: | ||

* New commands: grep, head, tail, wc | * New commands: grep, head, tail, wc | ||

* Redirect STDERR to /dev/null | * Redirect STDERR to /dev/null | ||

* Many commands can read from STDIN. E.g.: cat, less, tar, grep, head, tail | * Many commands can read from STDIN. E.g.: cat, less, tar, grep, head, tail | ||

* The STDOUT from one command can be piped to the STDIN of another | * The STDOUT from one command can be piped to the STDIN of another | ||

Revision as of 17:01, 7 March 2024

Input and Output

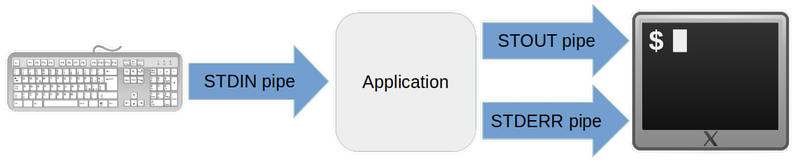

You need to study system programming to fully understand how input and output works, but without being a programmer you can still learn most of what you need to control input and output on the command line.

The introduction in this lab will probably be a little dry, but hopefuly it will start making more sense when you get to apply these concepts later in the lab.

Each application on a POSIX-compatible system (such as Linux) is always started with three data pipes attached to it. These are:

- Standard input (STDIN, file descriptor 0)

- Standard output (STDOUT, file descriptor 1)

- Standard error (STDERR, file descriptor 2)

The file descriptor numbers mostly won't matter to you in this course, but they're good to know for the future. You'll remember them if you just memorize STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR, and recall that the count starts from zero.

STDOUT

Standard output is the most straightforward to understand. Whatever normal output a command-line prints goes out through the standard output pipe.

By default the standard output pipe is connected to the terminal, and anything that goes into that pipe comes out as readable output on the screen.

STDERR

This is where things get complicated. The application can send output into STDOUT or STDERR. Both these pipes are connected to the terminal by default, and both outputs will look the same to the user. But they are different pipes - which means they are controlled separately.

One extra confusing factor is the definition of "error". Sometimes it's obvious what constitutes an error, but often it isn't.

The programmer who wrote the application had to make the decision which sort of output to send to STDOUT and which to send to STDERR. You can try and make an educated guess, but you'll have to confirm by experimenting.

STDIN

Standard input is only tricky until you become familiar with it. STDIN is also a data pipe, but by default instead of the pipe's input coming from the program and the output going to the terminal: the pipe's input comes from the terminal and the output goes into the program.

Up to this point in the course you haven't used STDIN, but it's used all the time and now is the time to learn about it.

Other pipes

A programmer can choose to open as many other pipes as they like in their application, but none of those extra pipes can be controlled using the mechanisms in this lab.

Redirecting input/output

The input/output pipes don't have to be connected to the default input/output (keyboard and terminal display). You can choose to connect one or two or all three of these pipes to something else. The something else can be:

- A file, which is commonly called redirection

- Another program, which is commonly called piping

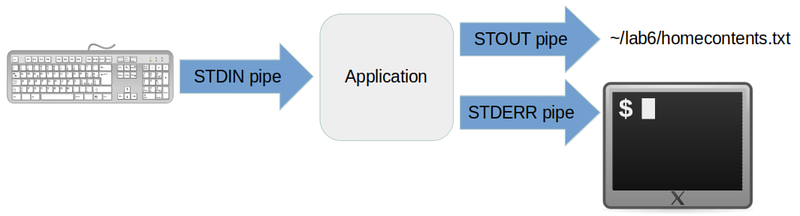

Redirect STDOUT to a file

When the shell encounters the character > it will interpret that as an instruction to redirect the standard output from the application you're running into a file.

A simple example of when you might use this is to save a listing of all the files you have now, so that you can do something with that list later.

- In a terminal create the directory ~/lab6 but keep your PWD in your home directory.

- Then run ls twice. The first time on its own, the second time redirecting its output to a file:

ls

ls > lab6/homecontents.txt

Note that the second time there is no output on the terminal. That's because you instructed the shell to redirect the standard output from the ls command into the file lab6/homecontents.txt:

The reason why homecontents.txt doesn't have any colours in it is simple: there's no such thing as dark blue or light green in a plain text file. There's just text. The more complicated question is where did the pretty colours come from when the output is in a terminal? That's too complicated a question for this course, and we're just going to ignore it.

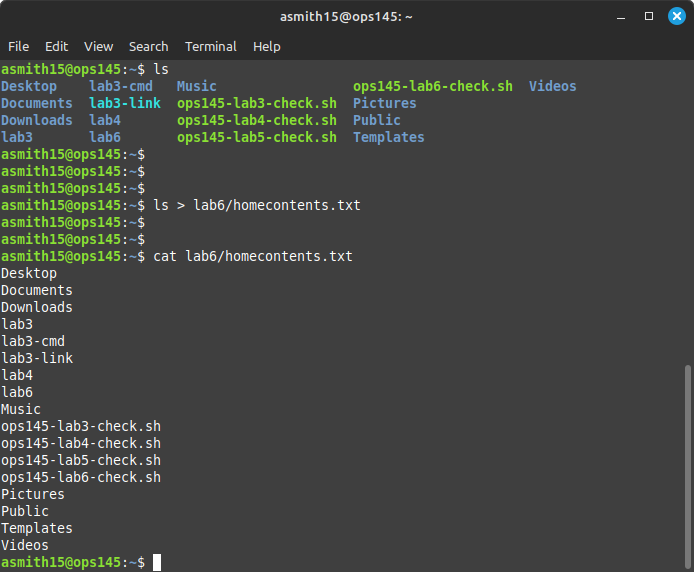

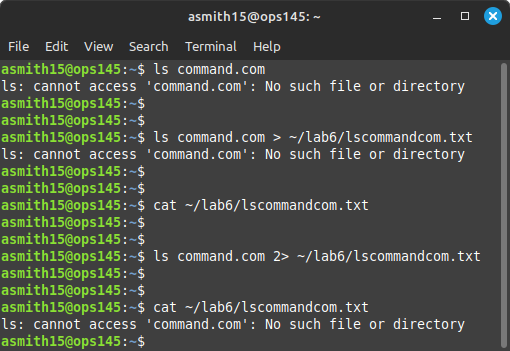

Redirect STDERR to a file

- Run an ls command, giving it as an argument a filename for a file which doesn't exist. For example:

ls command.com

- The command prints some output: "ls: cannot access 'command.com': No such file or directory". From experience I know that this comes through the STDERR pipe, but we can confirm by redirecting STDOUT to a file:

ls command.com > ~/lab6/lscommandcom.txt

- Note that the output is still printed in the terminal, and the file lscommandcom.txt is empty. There's really no way to see a difference between standard and error output except through experimentation like this.

- You can redirect STDERR to a file using the 2> notation (2 is the number of the pipe):

ls command.com 2> ~/lab6/lscommandcom.txt

Here's what all that looks like:

Because there's no obvious difference between standard and error output in the terminal: this distinction often causes headaches, but that's just a reality we have to deal with.

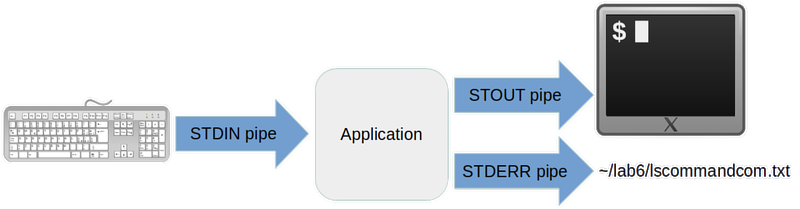

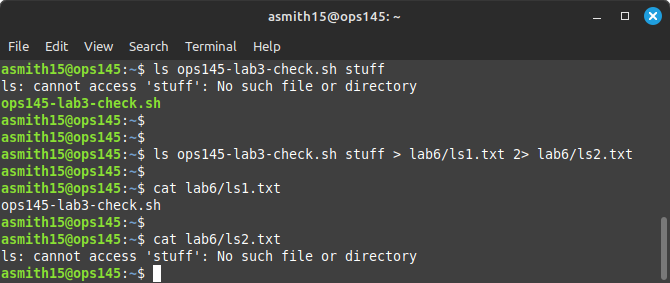

You can redirect STDOUT to one file and STDERR to another file:

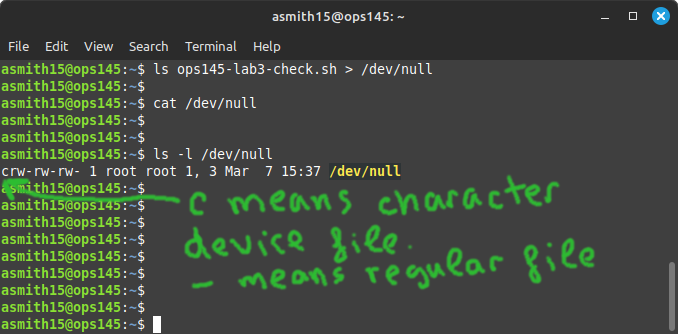

Redirect to /dev/null

/dev/null is a special device file on Linux machines. It's like a black hole: anything that goes into it just disappears for ever. It is frequently used when you want to run a command, but you're sure you don't want to see the output of that command, and you don't want to save that output either. The utility of this will become more obvious when we get to scripting.

For now you can practice with the ls command:

Also:

- New commands: grep, head, tail, wc

- Redirect STDERR to /dev/null

- Many commands can read from STDIN. E.g.: cat, less, tar, grep, head, tail

- The STDOUT from one command can be piped to the STDIN of another