OPS145 Lab 6 Newversion

Special characters in the shell

The terminal you've been using this whole time in the course is running an application called the shell. Specifically the bash shell.

This application (bash) has been written to interpret input from the user as some sort of a command; or as an argument; or as data. It's a very powerful application with many abilities, but almost all the user input comes from the keyboard.

There are only so many keys of the keyboard, and most of them are used to input human-readable characters. That means some of those characters will necessarily have multiple meanings. We will look at several such characters in this lab.

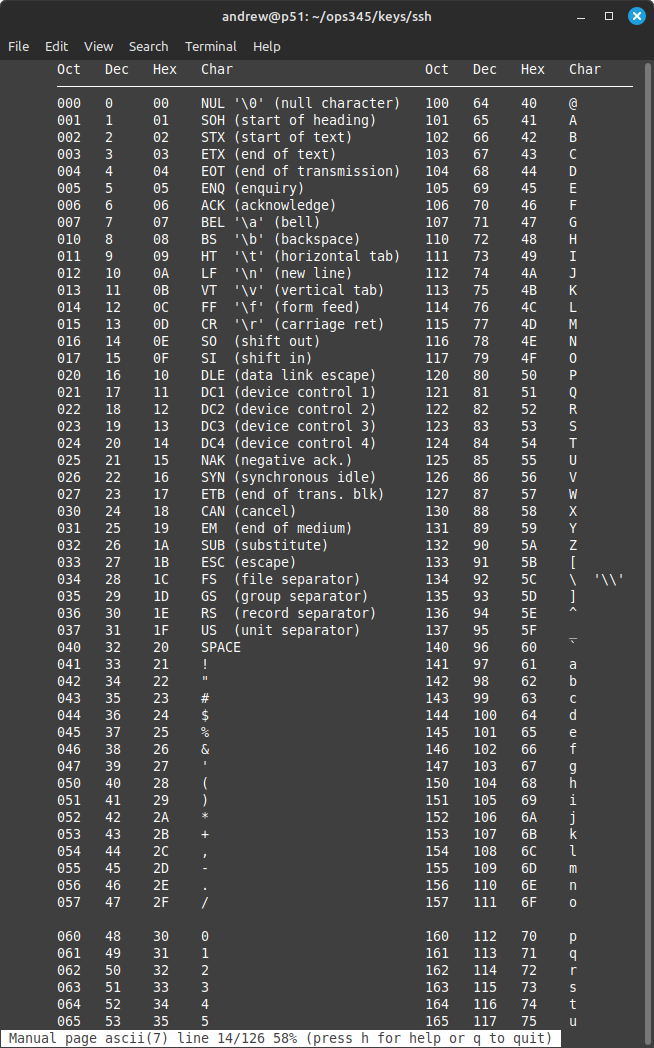

Here's most of the ASCII table (as much as I could fit on my screen). Note that most of the characters in this table are familiar to you, but some (especially the first 32) are probably brand new to you. You can see this table easily by running man ascii:

. and ..

Coming from the Windows world you might be used to the concepts of "filename" and "extension". If you're not too familiar with that: you should configure your windows to always show file extensions (it doesn't by default).

For example if you have a picture file called smily.jpg: You might call smily the filename, and jpg the extension. But then what is the dot? You could call it a separator, but In fact the dot is just as much part of the filename as smily and jpg. Looking at the ASCII table: s and m are just as different from each other as s and .

And what's the extension in a file called lab1.tar.xz? Is it xz? Or tar.xz? What about in a file called Dr. Evil plan.txt?

When it comes to filenames and extensions: the use of a dot as a separator is just a convention to help people organize their files, and is barely useful from a technological point of view.

But there's another use of dots in filesystems, which is much more fundamental. Every directory contains at least these two records: a link to itself (.), and a link to its parent (..)

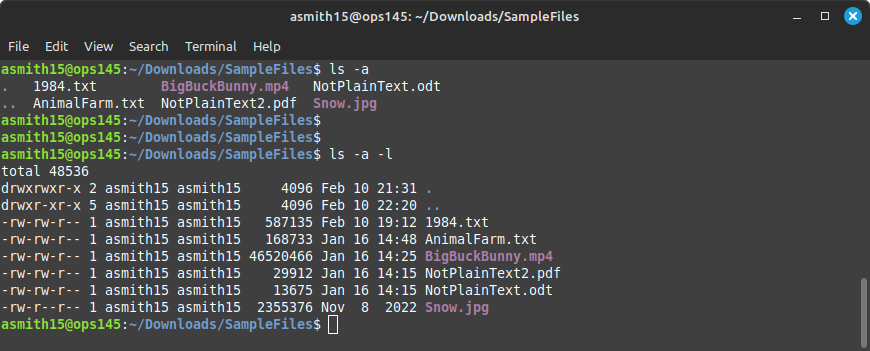

You can see these records when you run ls with the -a argument. Let's look at the SampleFiles directory you downloaded back in Lab 2:

- Open a terminal, and change the PWD to ~/Downloads/SampleFiles

- Run ls -a Note that in the output there is a . and a ..

- Run ls -a -l Note that the . and .. are directories.

- Remember that you can give an argument to ls telling it to show the details of a specific file or directory. For example ls -l 1984.txt will show details about that specific file, and ls -l / will show details for the immediate contents of the root directory.

- Run ls -l -a . (including the dot in the end) and note that it shows the same output as ls -l -a That's because:

- The ls directory will show the contents of PWD if you don't give it a specific path.

- Your PWD is ~/Downloads/SampleFiles/

- The . in SampleFiles points to itself (SampleFiles)

- Run ls -l -a .. and ls -l -a ~/Downloads Note that the output is the same. That's because:

- a

Special characters

- wget/tar instead of firefox/archivemanager

- .

- ..

- hidden files

- * and ? wildcards

- spaces in filenames

- single quotes

- double quotes

- \

- Back-quote does something else

- Revisit ls, cat, mkdir, rm, mv, cp with spaces and special characters

- Mismatched quotes

- Quotes to work with filenames with special characters, and other quotes