OPS245 Lab 4: Difference between revisions

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

*SD cards sometimes don't have any partitions, but if '''/dev/mmcblk0''' has one: its device name will be '''/dev/mmcblk0p1''' | *SD cards sometimes don't have any partitions, but if '''/dev/mmcblk0''' has one: its device name will be '''/dev/mmcblk0p1''' | ||

Other than the kernel: everything in a Linux system can use a block storage device the same way no matter what it is. You can put a filesystem on a partition on a SATA drive, or on an entire SSD drive. After you configure it: the user will never be aware what sort of device is used to store their files. | Other than the kernel: everything in a Linux system can use a block storage device the same way no matter what it is. You can put a filesystem on a partition on a SATA drive, or on an entire SSD drive. After you configure it: the user will never be aware what sort of device is used to store their files. | ||

There are several tools available to work with partitions on Linux. '''Gparted''' is a graphical tool that's very comfortable to use, and it also lets you format your partitons (put a filesystem on them). In command-line mode there are '''cfdisk''', '''parted''', '''fdisk''', and a bunch of other command-line-only tools. Other than cfdisk they are all pretty horrible to use. | |||

== Filesystems == | == Filesystems == | ||

| Line 41: | Line 43: | ||

While Linux can read and write DOS/Windows filesystems: they are rarely used (except for USB sticks and SD cards) because those filesystems don't store all the information a Linux system would like to have (for example there are no permissions of any kind available on a FAT32 filesystem). | While Linux can read and write DOS/Windows filesystems: they are rarely used (except for USB sticks and SD cards) because those filesystems don't store all the information a Linux system would like to have (for example there are no permissions of any kind available on a FAT32 filesystem). | ||

Putting a filesystem on a storage device is usually called '''formatting'''. | |||

== Mounting == | |||

After you have a storage device connected to your Linux box, and you set up the partition(s) on it, and you formatted those partitions: you need to do one more step to be able to save files on that device and read them back. You need to connect the device to your Linux filesystem tree: that's called '''mounting'''. | |||

Linux doesn't use drive letters. Every storage device is accessed by a directory path that always starts with '''<code>/</code>''' (root). That root has nothing to do with the user root, it's unfortunate that the same word is used for completely different concepts on the same system. It's sometimes called the filesystem root, though that's not completely technically correct. | |||

That's relatively straight-forward when you only have one storage device. It takes some understanding to get used to what happens when you're using multiple storage devices at the same time while you system only have one root. | |||

* For a quick demonstration of this concept: in your '''server1''' run <syntaxhighlight lang="bash">mount | grep sda</syntaxhighlight> | |||

[[File:MountGrepSda.png|800px|border|center]] | |||

*Worstation: | *Worstation: | ||

Revision as of 16:35, 3 February 2023

!!! THIS LAB IS NOT READY YET !!!

In this lab we're going to look at how storaged is accessed and managed in Linux, and traditional partitioning setups (both MBR and GPT).

Storage devices

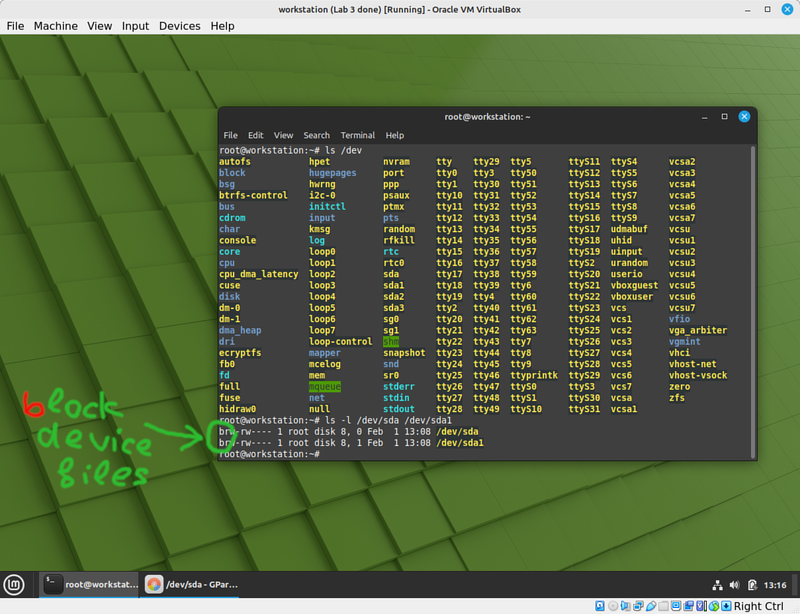

In Linix every block storage device (a hard drive, optical drive, USB stick, etc.) is assigned a device file. This is not the type of file you're used to, it's not saved somewhere. It looks like a file in a directory, but in fact it's just a means for you (the administrator) to control the device.

You will find such device files in /dev:

Usually:

- SATA drives and USB sticks have device files that start with /dev/sd, and the last letter is the number of the drive. So /dev/sda is the first one, /dev/sdb is the second one, etc.

- SSD drives usually have more complicated device names that start with /dev/nvme0n, with a number in the end. So /dev/nvme0n1 is the first drive, /dev/nvme0n2 is the second drive, etc.

- SD cards have different complicated device names that start with /dev/mmcblk, with a number in the end. So /dev/mmcblk0 is the first drive, /dev/mmcblk1 is the second drive, etc.

- Old IDE drives' device names start with /dev/hd. You don't see these much any more.

Luckily for you: VirtualBox emulates a SATA interface by default, so you'll see the /dev/sd* type of device names for your drives.

When you add a new drive to a running system (if the drive is hot-pluggable): it will be assigned the next unused number/letter. On a cold boot the device file name is not completely reliable, because the order of the drives is determined by which port they're plugged into, rather than anything unique to the drive itself.

You can't expect to know what your storage device name is without looking in the /dev directory to see what's there, especially on a virtualized system where you don't have either a physical controller nor a physical storage device (both are emulated by your hypervisor).

Partitions

You might already be familiar with the concept of a partition: it's a region of a storage device that's treated independently of other partitions.

Partitions are also assigned device files, since the things you can do with a partition are nearly identical to the things you can do with a storage device. So for example:

- If your SATA drive /dev/sda has two partitions: the first one is /dev/sda1 and the second is /dev/sda2. We'll ignore extended partitions and logical drives since they're nearly obsolete already and the complicate this numbering.

- If your SSD drive /dev/nvme0n1 has two partitions: the first one is /dev/nvme0n1p1 and the second is nvme0n1p2.

- SD cards sometimes don't have any partitions, but if /dev/mmcblk0 has one: its device name will be /dev/mmcblk0p1

Other than the kernel: everything in a Linux system can use a block storage device the same way no matter what it is. You can put a filesystem on a partition on a SATA drive, or on an entire SSD drive. After you configure it: the user will never be aware what sort of device is used to store their files.

There are several tools available to work with partitions on Linux. Gparted is a graphical tool that's very comfortable to use, and it also lets you format your partitons (put a filesystem on them). In command-line mode there are cfdisk, parted, fdisk, and a bunch of other command-line-only tools. Other than cfdisk they are all pretty horrible to use.

Filesystems

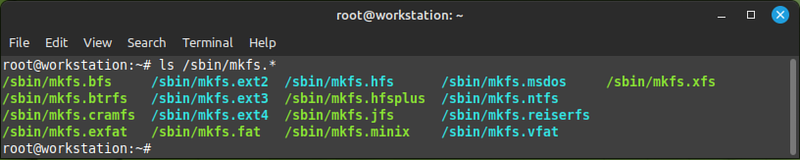

Block devices only store blocks of bytes, indifferent to what you believe the meaning of those bytes is. They are too stupid to store interesting things like filenames, directories, permissions, or even the size of a file. To save all that information: a filesystem is used.

There are many filesystem types available, and Linux supports just about all of them. But in this course we'll work primarily with ext4 filesystems. You can see which filesystems you can use on a default installation of Linux Mint by running ls /sbin/mkfs.*

While Linux can read and write DOS/Windows filesystems: they are rarely used (except for USB sticks and SD cards) because those filesystems don't store all the information a Linux system would like to have (for example there are no permissions of any kind available on a FAT32 filesystem).

Putting a filesystem on a storage device is usually called formatting.

Mounting

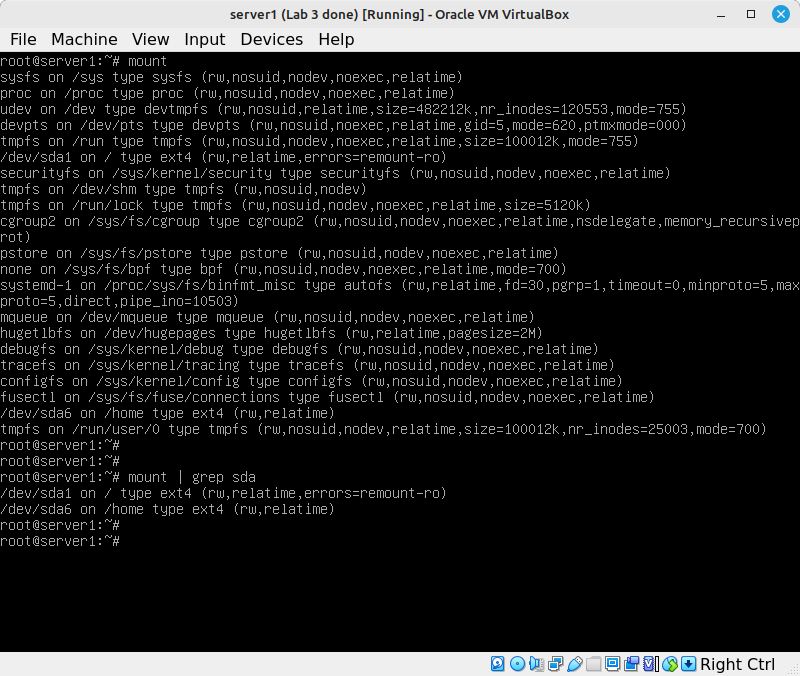

After you have a storage device connected to your Linux box, and you set up the partition(s) on it, and you formatted those partitions: you need to do one more step to be able to save files on that device and read them back. You need to connect the device to your Linux filesystem tree: that's called mounting.

Linux doesn't use drive letters. Every storage device is accessed by a directory path that always starts with / (root). That root has nothing to do with the user root, it's unfortunate that the same word is used for completely different concepts on the same system. It's sometimes called the filesystem root, though that's not completely technically correct.

That's relatively straight-forward when you only have one storage device. It takes some understanding to get used to what happens when you're using multiple storage devices at the same time while you system only have one root.

- For a quick demonstration of this concept: in your server1 run

mount | grep sda

- Worstation:

- add disk

- use gparted

- create gpt, two partitions: /srv/goodstuff and /srv/greatstuff

- mount manually

- add both to fstab

- fill first partition

- delete second partition, resize existing one, recreate second partition

- server1:

- fill /home/alpha

- add a disk

- partition it

- mount in temporary place, move all the files from /home/alpha to it

- edit fstab, reboot

- see how much space alpha and beta have

- lvm overview