OPS345 Lab 5: Difference between revisions

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

You can't get a publicly-resolvable domain name just by doing some magic on your server. You need to pay a registrar (usually a yearly fee of around 20$) to connect your records to the global DNS network. | You can't get a publicly-resolvable domain name just by doing some magic on your server. You need to pay a registrar (usually a yearly fee of around 20$) to connect your records to the global DNS network. | ||

Wikipedia sometimes has useful information, and the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System#Address_resolution_mechanism Address resolution mechanism section] has a reasonably comprehensible diagram and description of a simple query process. | Wikipedia sometimes has useful information, and the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System#Address_resolution_mechanism Address resolution mechanism section] of its DNS page has a reasonably comprehensible diagram and description of a simple query process. | ||

You would typically be interested in controlling somedomain.com (or .ca or .org, etc.) and therefore you would: | You would typically be interested in controlling somedomain.com (or .ca or .org, etc.) and therefore you would: | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

{{Admon/important|Mind the dots|Technically every FQDN in DNS ends with a dot, it's just normally hidden from the users. Try it in a web browser, using ping, etc. When you're configuring DNS records: pay attention whether your host/value has a trailing dot or not. If you're missing the trailing dot: your value will have your domain appended to it. Practice it to understand what this means.}} | {{Admon/important|Mind the dots|Technically every FQDN in DNS ends with a dot, it's just normally hidden from the users. Try it in a web browser, using ping, etc. When you're configuring DNS records: pay attention whether your host/value has a trailing dot or not. If you're missing the trailing dot: your value will have your domain appended to it. Practice it to understand what this means.}} | ||

* Test your two new records you just created using dig. If you're not sure whether the problem is with caching: you can query the authoritative DNS server directly, e.g.:<syntaxhighlight lang="bash">dig asmith15.ops345.ca @ns1.littlesvr.ca</syntaxhighlight> | * Test your two new records you just created using dig. If you're not sure whether the problem is with caching: you can query the authoritative DNS server directly, e.g.:<syntaxhighlight lang="bash">dig asmith15.ops345.ca @ns1.littlesvr.ca</syntaxhighlight> | ||

* You can also use Dig through the [https://toolbox.googleapps.com/apps/dig/ Google Admin Toolbox] to test your DNS settings. | |||

* You should also be able to go to www.yourusername.ops345.ca in a web browser: | * You should also be able to go to www.yourusername.ops345.ca in a web browser: | ||

| Line 87: | Line 88: | ||

== Access your Nextcloud via FQDN == | == Access your Nextcloud via FQDN == | ||

{{Admon/tip|Your database might be off|If you followed my advice: your database instance should be temporarily stopped. That means you can't access it, and neither can a web application like Nextcloud. To restart your database instance: find it in the RDS interface and pick "Start" from the Actions menu. Depending on how much of the 50$ credit you've used up: you might want to stop it again after you're done with this lab.}} | |||

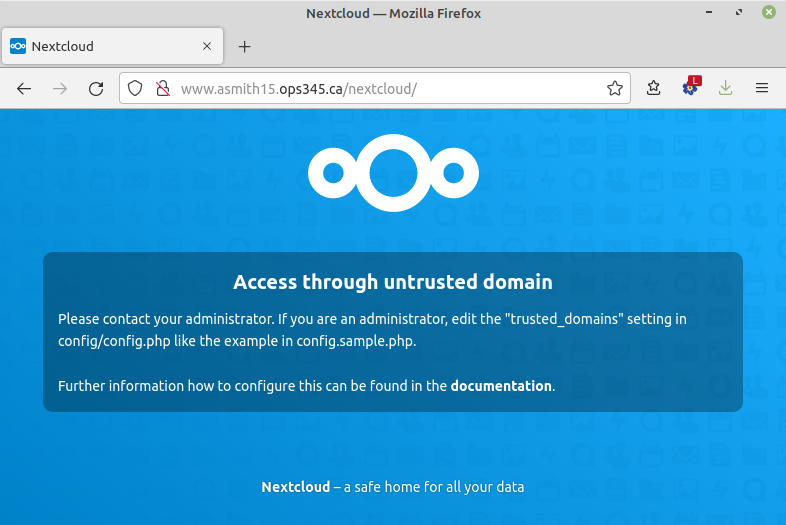

* Try to go to www.yourusername.ops345.ca/nextcloud in a web browser. You should see an error like this: | * Try to go to www.yourusername.ops345.ca/nextcloud in a web browser. You should see an error like this: | ||

| Line 93: | Line 96: | ||

* Since you are the administrator: there's noone else for you to contact. Good thing you've had a little bit of practice with PHP. Fix the error so that you can log in to your Nextcloud installation. [https://help.nextcloud.com/t/howto-add-a-new-trusted-domain/26 This Nextcloud help page] might help too. | * Since you are the administrator: there's noone else for you to contact. Good thing you've had a little bit of practice with PHP. Fix the error so that you can log in to your Nextcloud installation. [https://help.nextcloud.com/t/howto-add-a-new-trusted-domain/26 This Nextcloud help page] might help too. | ||

'''The next time you'll need your database for sure is for Assignment 2 (scheduled more than a month from now).''' I suggest you write some notes for yourself to stop your database instance three or four more times in the meantime. | |||

= Submit evidence of your work = | = Submit evidence of your work = | ||

| Line 224: | Line 104: | ||

* A dig query for your A record. | * A dig query for your A record. | ||

* A dig query for your CNAME record. | * A dig query for your CNAME record. | ||

* Firefox showing http://yourusername.ops345.ca/nextcloud/ | * Firefox showing http://yourusername.ops345.ca/nextcloud/ | ||

[[Category:OPS345]] | [[Category:OPS345]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:07, 5 September 2024

DNS overview

The Domain Name System converts human-friendly domain names to IP addresses. Computers on the internet can only communicate with each other using IP addresses. But people aren't very good at remembering long strings of numbers (up to 12 digits for ipv4) or even longer strings of numbers and characters mixed (24 characters for ipv6).

Therefore DNS is a critical part of the internet infrastructure, and just about everyone who has a website needs to do something with it. Some all-inclusive web hosts offer domain name registration and automatically connect their hosting service to the domain registration, but that comes at the cost of any flexibility. From a technical point of view your domain name registration has nothing to do with the server that your DNS records are pointing to.

DNS records

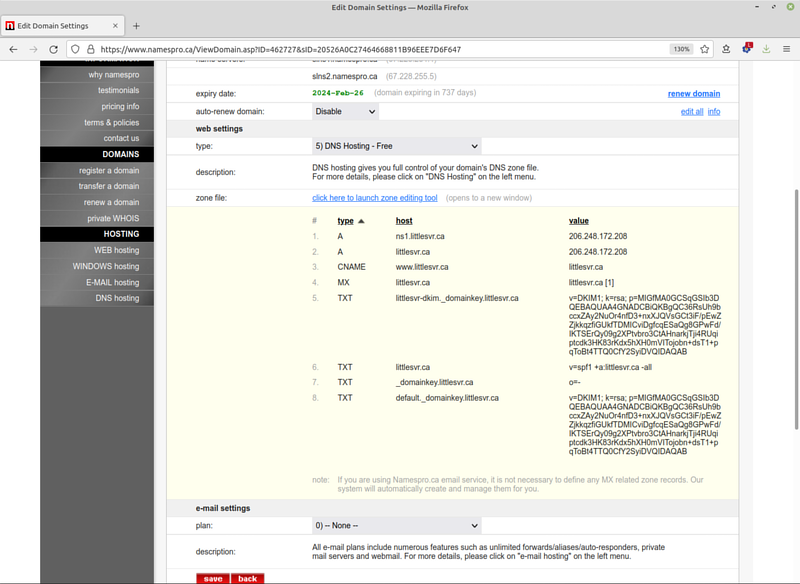

DNS servers store records of different types. Here are the ones you'll see most often:

- A records (the most common ones) map fully-qualified donain names (FQDNs) to IP addresses.

- CNAME records (also called aliases) map a name to another name.

- MX records store the FQDN of the mail server for that domain.

- TXT records can store almost anything and are often used for various security features.

You can use several command-line tools to query DNS servers. Some are more useful than others. Try the following:

- Notice that ICMP (ping) packets are sent to an IP address, not the FQDN. That means the ping command had to first do a DNS query (for the A record for littlesvr.ca) and therefore this is a simple way to do a DNS query, which is useful if you don't have any better tools. Notice also that this works even if the server won't respond to pings, or even if it's offline.

ping littlesvr.ca

- This is a much more DNS-specific command and has parameters that will let you ask for different record types.

host littlesvr.ca host -a littlesvr.ca

- This is the one we'll use mostly in this course. The output is the most difficult to read, but the details it provides are useful when troubleshooting your DNS setup. The first dig command above asks for the A record (the default). The second asks for the MX record for littlesvr.ca. The third asks for the A record from a specific DNS server (8.8.8.8).

dig littlesvr.ca dig littlesvr.ca MX dig littlesvr.ca @8.8.8.8

- Do your best to construct DNS queries using dig to get all the records set up for littlesvr.ca. Following is a screenshot of the registrar's interface:

If you can't obtain all these records using dig: you either don't understand how DNS works or you need more practice with dig. Keep trying until you figure it out.

Registering a domain name

You can't get a publicly-resolvable domain name just by doing some magic on your server. You need to pay a registrar (usually a yearly fee of around 20$) to connect your records to the global DNS network.

Wikipedia sometimes has useful information, and the Address resolution mechanism section of its DNS page has a reasonably comprehensible diagram and description of a simple query process.

You would typically be interested in controlling somedomain.com (or .ca or .org, etc.) and therefore you would:

- Find a registrar who's authorized to sell domains under that TLD (top-level domain), which is .com in this example.

- Check whether somedomain.com is available.

- If it's available: you pay the registrar and in return you get exclusive control over the DNS records for that domain for the period of time you paid for.

- If it's not available: you're most likely out of luck. It can cost tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy a domain from someone who already bought it.

- You can add whatever DNS records you want for your domain, and you also control all the subdomains of that domain. You won't need to pay extra for one.two.three.four.somedomain.com

- After you add you records - they will be available to the world almost immediately. Except: see next section.

If you're a more advanced user: you can configure your domain records to be stored on and served by your own DNS server(s). You won't be doing that in this course. It's a lot of hard work and requires a cooparative registrar to set up glue records for you.

Caching

Because DNS is used so much (see a typical webpage): there are countless DNS queries done everywhere all the time.

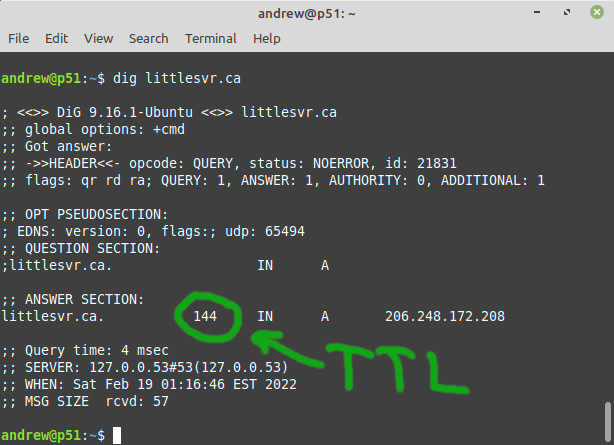

The responses to those queries are cached (stored closer to the questioner) in order to minimize load on the authoritative servers. They are cached for a specific amount of time - typically controlled by the domain owner, though cheaper registries have minimum limits.

That means that if you have an A record linking somedomain.com to 1.2.3.4, and someone does a DNS query for somedomain.com: their next query for somedomain.com will not make it to your DNS server until after the TTL expires.

That means if you change your A record to link somedomain to 2.3.4.5 instead: it may take as long as 48 hours for everyone in the world to be guaranteed to get the new record. You can see the TTL (in seconds) for a record when you use dig to do a query:

There are websites available that can help you figure out whether your records are up to date around the world, for example https://www.whatsmydns.net/

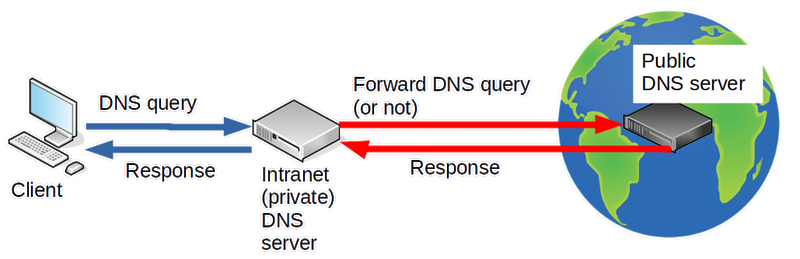

Private DNS

If you only need DNS records inside your organization (e.g. on an LAN/intranet): you can avoid paying a registrar for each domain.

You do that by running a DNS server on your LAN, and making sure all the machines on that network are configured to use your internal DNS server. Curiously: in such a setup the administrator can have control over all DNS records including for domains owned by someone else:

Your DNS records

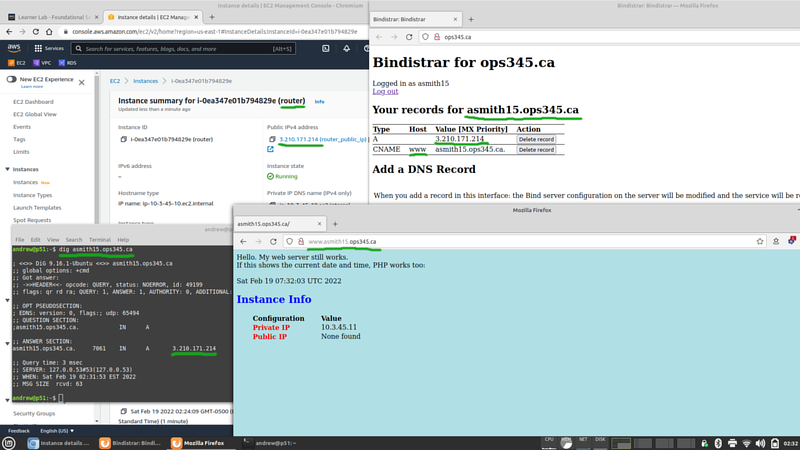

In this course you'll get to experience something like a real domain registration process with some limitations:

- You'll get full control over a subdomain of ops345.ca (e.g. asmith15.ops345.ca), rather than a second-level domain (like asmith15.ca).

- You can only create A, MX, CNAME, and TXT records.

- You have no control over the TTL.

But you get to do this for free.

You should have received an email about a Bindistrar account that's been created for you. The email will include your username and a random password. Please keep the password secret. You cannot change it. I can change it for you but I'd really rather not.

After you log in: Bindistrar will allow you to create public DNS records for yourusername.ops345.ca

- Set up an A record for yourusername.ops345.ca to point to your elastic IP (the one assigned to router).

- Set up a CNAME record for www, so that it points to yourusername.ops345.ca

- Test your two new records you just created using dig. If you're not sure whether the problem is with caching: you can query the authoritative DNS server directly, e.g.:

dig asmith15.ops345.ca @ns1.littlesvr.ca

- You can also use Dig through the Google Admin Toolbox to test your DNS settings.

- You should also be able to go to www.yourusername.ops345.ca in a web browser:

Access your Nextcloud via FQDN

- Try to go to www.yourusername.ops345.ca/nextcloud in a web browser. You should see an error like this:

- Since you are the administrator: there's noone else for you to contact. Good thing you've had a little bit of practice with PHP. Fix the error so that you can log in to your Nextcloud installation. This Nextcloud help page might help too.

The next time you'll need your database for sure is for Assignment 2 (scheduled more than a month from now). I suggest you write some notes for yourself to stop your database instance three or four more times in the meantime.

Submit evidence of your work

For this lab, please submit screenshots that show you've completed the work, unless your professor has given you different instructions. As a minimum that's:

- A dig query for your A record.

- A dig query for your CNAME record.

- Firefox showing http://yourusername.ops345.ca/nextcloud/